AI is Eating India's Growth Story

India dreams of being a “viksit” (developed) country by 2047. Artificial Intelligence kills the pillar on which that dream is built: India’s service sector.

Source: Pixabay

In Delhi, there’s a huge office complex not far from where I live. Shining, gleaming, newly built. It is abuzz with skinny, spectacle-wearing, clean-shaven men. They enter as a swarm at 9 on the dot on each weekday, often hastily disembarking off their scooters, rickshaws, taxis. Ride through any major Indian city, and you’ll find the exact same sight. Like clockwork, giant towers are erected, signposts with the word “TCS”, “Infosys”, or “HCL” are lit, and fresh college graduates pour in. Economies build around these swarms. Condominiums, malls, railroads, e-commerce apps, and banks all emerge in unison, satiating every craving of theirs.

This is India’s growth story, and AI is here to smash it to pieces — and with it, the dreams of millions. Here’s how.

India’s Obsession with Services

While East Asia built factories, India built offices. Indeed, Manufacturing forms a smaller and smaller part of the Indian economy:

Fig 1. Manufacturing, Value Added (% of GDP): India, China, Vietnam (World Bank)

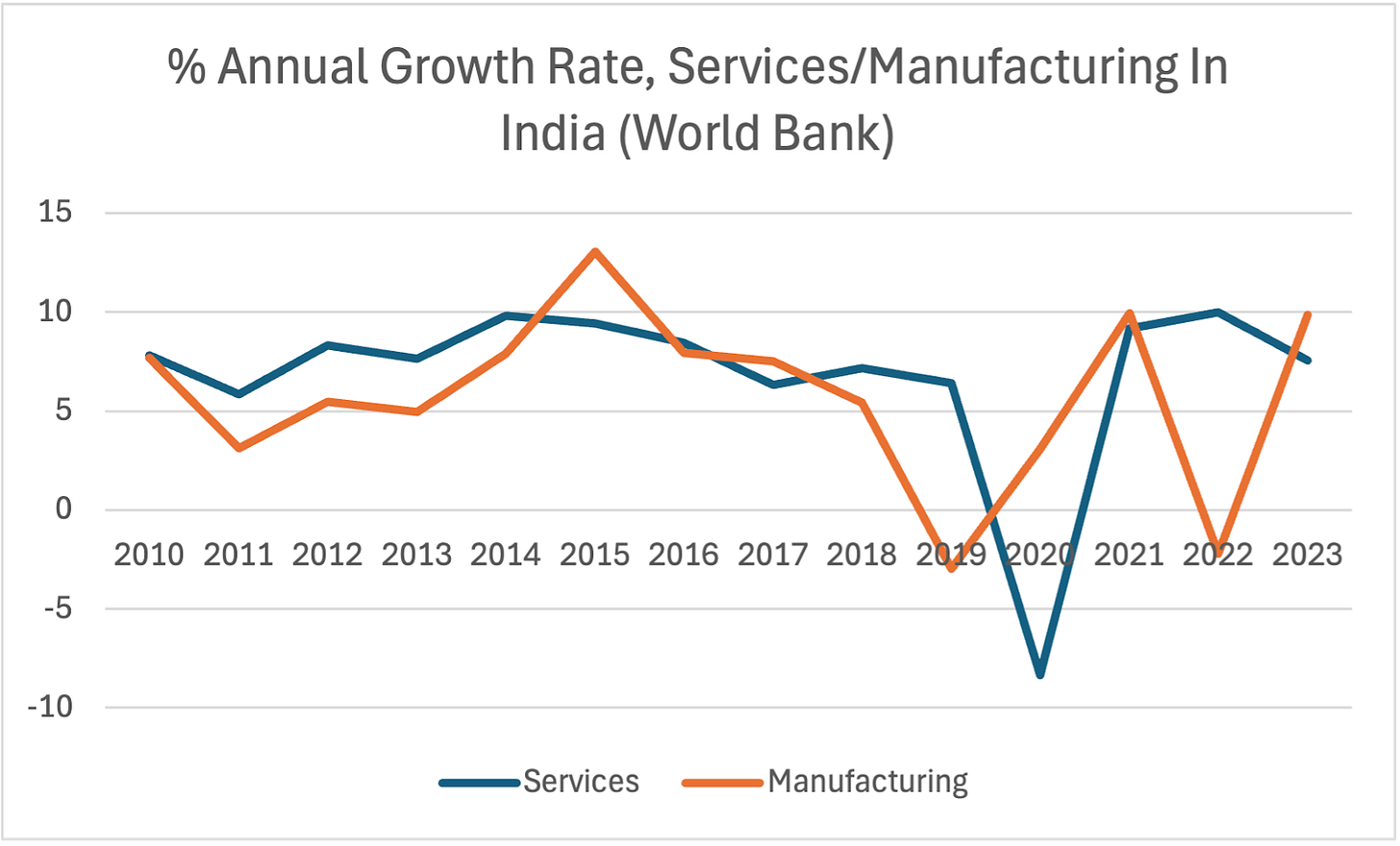

Instead, the services sector, which includes things like IT, fuels India’s growth:

This trajectory is abnormal: economic development usually follows the path of agriculture -> manufacturing -> services. For example, Vietnam grew through manufacturing, and only now it has begun to switch to services. India has skipped this step. Today, services are about half of India’s Economy.

Within services, IT and Professional work stand out:

Figure 3. Sectoral Share of Services Sector in terms of GVA, exports, employment (Economic Survey 2024-25)

And the buyers of those services aren’t Indian, but foreign:

Figure 4. Revenue Growth of IT-BPM Sector (in US$ Billion), IBEF

The foreigners don’t make Indian engineers do cutting edge work. They make them do mundane, low-skill work instead:

Figure 5. Export Revenue Growth by Sector (in US$ Billion), IBEF

Specifically, these offices mostly do back-office, labour-intensive work. Things like customer support, data labelling, and claims management.

How did India get here? Well, the answer is complex. For one, manufacturing in India used to be really difficult. Firms had to deal with bureaucracy, labour laws, and bad infrastructure. They couldn’t get permission to begin, hire and fire workers, power their factories or transport their goods. It has been getting better, but it’s still far behind countries like Vietnam.

Another reason is that services suited India well. Many people in India speak English. It also has great college education, but bad primary education. This makes its population spiky. A decent number of great, english-speaking graduates, but a large number of low-skilled workers. Not a lot in the middle. Manufacturing requires a lot of semi-skilled workers, the exact kind India didn’t have.

This meant that India kept growing and growing on the back of its english-speaking graduates. The others work on farms, like they did 300 years ago. And thus, two Indias emerged. India 1 is a fast-growing, bustling metropolis, and India 2 is stagnant farmland.

But India’s college education was not amazing. Its graduates were only serviceable. They could do back-office work, but could not build companies like Google. The truly amazing talent moved to the West. Indian companies did what they could with the remaining talent. They built empires on doing back-office work for cheap. As Indian talent slowly got better, they slowly began doing more advanced work. Slowly.

But they still mostly do back-office work. And that’s a huge problem.

AI is ending the Back-Office

Why is this a problem? Well, AI is the back-office now. Here’s what a16z, a leading VC, had to say:

We believe there is a clear opportunity with AI to productize and unbundle the BPO. This is exciting for several reasons. From a technical perspective, there’s a clear “why now”: modern AI has become exceptionally good at handling work that couldn’t previously be done adequately with software. Core foundation models are rapidly getting better at data extraction, deep research, and complex reasoning, while voice AI agents are mature enough for large-scale production with browser agents soon to follow. From a business perspective, BPOs tend to be older incumbents that lack cutting-edge tech and operate in a well-defined category of work with clear, existing budgets; this makes them prime disruption targets for startups given the proven market need, available budget, and legacy competition.

a16z, “Unbundling the BPO: How AI Will Disrupt Outsourced Work”

Indeed, Silicon Valley is busy. It’s creating voice agent startups which can replace call centers. Data companies which can replace human labelling. AI insurance agents which can replace arguing with a human. Coding agents like Cursor Composer and Replit which can replace simple coding jobs. Similarly, other startups are hard at work replacing all other work at the Indian IT back-offices.

And India’s IT giants agree that AI is big. TCS, Infosys, HCL brag about AI and GenAI in their reports. They have to: their customers are asking for it.

The disruption will be gradual. Here’s what Aravind Srinivas, the founder of Perplexity, had to say:

They’re not going to hire as many people going forward … They’ll have to charge less. Some of it is actually based on relationships. [A customer might say that] I know AI can do some of these things, but I’ll still trust [Indian IT firms] to do it without any bugs or errors. Until AIs are at a point of reliability where you have no arguments to use them, I feel humans will still trust human businesses to do stuff for them. They’ll just push them to be like, hey, now that AIs can [be used], why do you need three months to get it done? Get it done faster. Why do you guys need to charge us this much? Charge us slower.

At first, the technology will just help each employee. But soon, it will replace the most basic work, which will slightly reduce hiring. And then more work: you’ll just be a supervisor prompting and watching the AI. Moderately reduced hiring. And then even more work: the entire back-office will be replaced. No supervision needed, thus no Indian outsourcing needed.

Some might say that human jobs won’t be completely replaced. Only “augmented”. Well, you would need fewer workers as AI increases the productivity of each worker. The customers of the IT firms are slow, legacy businesses: they operate in insurance, healthcare, finance. They have a mostly stagnant amount of work to do. And if each worker does more when the amount of work stays the same, you would need fewer workers. This reduces the cost advantage of Indian labour, as AI/cloud expenses make up an increasing portion of costs.

How does the Indian Back-Office respond?

Well, they have two choices, and they are bad either way.

IT firms help clients implement AI solutions made by Silicon Valley companies.

IT firms create their own AI solutions.

Choice 1: Make themselves Redundant

Most have chosen the first. Clients are bringing AI into their processes using the IT firms’ higher-skilled arm.

While these IT firms do make money by helping their clients implement AI, they also end up killing their own business model. Currently, these IT giants charge clients per-hour-worked, per-employee, or per-action (eg. per call). They operate more like a law firm and less like Google or Salesforce — they offer a service with recurring revenue, not a product. However, AI turns these services into a product.

For example, implementing an LLM-powered chatbot for customer support for a client means that a firm cannot charge for every query they resolve with their human agents. The client pays OpenAI or Microsoft for resolving their query, the companies who run the AI models on their servers, and not TCS — they just had a one-off job of implementing the chatbot.

Gradually, the IT firms are automated away. There are a finite number of businesses who need to switch to AI. Businesses in the future will be AI-native, built from the ground up with the very AI capabilities these IT firms try to add. And thus, the IT firms will become relics of the past. They’ll have no customers to service.

Choice 2: Compete

If not, IT firms could create their own AI products. However, this is extremely difficult for the IT firms to do.

In essence, this means competing with all of the American tech giants, B2B SaaS companies, and budding startups. This is an extremely difficult task. While these firms do have client relationships and market knowledge, they do not have the talent.

The IT firms select for explicitly average talent. The advantage they offer is cheap labour costs, which means small salaries for its workers. Therefore, they don’t have the kind of exceptional talent to build exceptional products — that talent is expensive. The tech giants, quant firms, and startups pay well, so the exceptional talent ends up there. It does not end up at the IT firms. And because the talent is average, the vast labour force of the IT firms cannot simply be reallocated to building exceptional AI products.

Even if the Indian IT firms shifted to recruiting exceptional talent, they would be competing with not just other IT firms, but all tech companies. Western firms have set up Global Capability Centres (GCCs) and increased operations in India, which gives them access to this exceptional talent. The demand for this talent makes it more expensive, and that erodes the entire business proposition of the IT firms — cheap labour.

Even if the IT firms get the talent, they have other disadvantages. To create competitive AI products at scale, you need data centers. The West has an almost complete monopoly on data center capacity. This gives them the ability to vertically integrate. Microsoft or Google can optimize their own data centers to suit their offerings. Google can upgrade its data centers to TPUs to run AI. However, the IT firms, which have paltry data center capacity, will have to wait for a third party offering.

Maybe they could collaborate with Indian datacenter providers. However, even the Indian providers like Reliance are only engaging with Western firms for now.

Can India innovate?

Maybe I have it all wrong and India is actually really innovative. Maybe it can compete with Silicon Valley. Unfortunately, this seems really unlikely in its current form.

Figure 4. Global vs. Indian R&D (FAST India)

Ironically, India’s software industry is the least innovative major industry in India. The median global firms in software spend 46 times more on R&D than Indian firms, even when adjusted for profit. Remember, the top Indian talent is funneled into software. And it produces a lot of talent.

The simple truth is that India’s IT sector is a rent-seeking albatross which cannot innovate. By any metric, as a percentage of profit or revenue, the Indian IT firms spend paltry amounts on R&D. TCS, India’s largest IT firm, spent only 1.1% of revenue last financial year on R&D. It was a similar story the year before. And the year before that. They have no excuse. They simultaneously had a net profit margin of ~20%. In the US, R&D spend as a percentage of revenue is often in the double-digits.

These firms, as seen earlier, constantly tout AI and GenAI, but rarely back up their words with actual spending. And even if they have golden opportunities to, they fail. Infosys willingly gave up the opportunity to be involved in OpenAI. Remember, it was one of its earliest donors, and it could have continued this involvement when OpenAI created a for-profit entity.

If India’s established companies cannot innovate, what about its startups?

Well, at that point, they have no advantage over Western startups. For example, they would not have any of the long-lasting client relationships and name recognition the traditional IT firms have. They would be in a race with Western startups with no meaningful head start. And that’s a really hard race to win.

Silicon Valley is a machine. Y Combinator, a pre-seed VC and founder bootcamp, funded 633 startups related to the keyword “AI” in the past year. They funded 767 startups in total — 82% of the startups they funded were in AI.

India lags behind. Peak XV’s Surge, an Indian analogue of Y Combinator, only had 4 AI startups out of the 14 total startups in its latest batch. The WTFund, a non-dilutive grant for aspiring young founders, had 9 startups in its latest cohort. Only 3 extensively use AI.

The sheer, raw output of Silicon Valley will overwhelm Indian innovation at this rate. And these Silicon Valley upstarts have a better funding landscape, more M&A opportunities, and greater talent density. It seems almost inevitable that the center of the back office will move westward.

India’s Economy without a Back Office

So, what does India’s macroeconomic future look like with the loss of the back-office

Precarious.

Service exports subsidize India’s goods imports. India’s goods imports exceeded its goods exports by US$80 Billion in the last three months of 2024. The main thing allowing India to import so much is that it explores a huge amount of services, like IT. It exported US$50 billion more services than it imported in those three months.

This is not a huge problem by itself. After all, even America has the same imbalance. However, India is not a global financial hegemon. The US brings in a huge amount of portfolio and direct investments from abroad, and this allows it to run its huge trade deficits. India has no such option. Its portfolio and direct investment figures are very volatile. FDI has barely grown since the late 2000s.

The collapse of Indian IT will ruin this equilibrium. This is the equilibrium on which the rupee’s value rests. If the deficit grows, and the investments stay the same, the rupee will crash. After all, only 10% of TCS’ revenue came from within India.

Not only would the collapse of Indian IT reduce service exports, it would also increase service imports. When human labour becomes less important, we will have to run AI models on the cloud. The clouds, of course, will be running in the USA. American companies take money in US$, thereby increasing our imports. This will cause the rupee to depreciate. It’s hard to say by how much, but I would put money on 1 USD = 100 INR by 2027. It is 1 USD = 85.5 INR when I write this article.

In the short-term, this rebalancing in India’s balance of payments will cause slower economic growth. IT spend abroad will go to American big-tech and new-age startups instead of India. The IT giants would hire less, which means less consumer spending in the economy. Their profit margins would reduce, which means less investment in the economy. Foreign investors will flee India’s stock market as India’s already dampened stock market dampens even further because of these repercussions. I would guess that India would grow at 5% instead of the 6-7% at which India is usually forecasted for.

Privately, some VCs I have talked to convey similar sentiments. Here’s what a partner at a leading Indian VC firm said to me.

There is only so much you can put in a public report given it is not mine as much as [VC firm’s] interests I need to keep in mind. Privately I am v worried abt AI and its implications for India, especially on its potential to disrupt the outsourcing Industry. AI sovereignty will not be easy too I feel.

How does India fix itself?

There is one obvious advantage to a weaker rupee.

A depreciated rupee makes India’s manufacturing more competitive. Foreign buyers pay less in their currency for India’s manufacturing exports. Indians have more expensive imports, which incentivises domestic manufacturing.Thus, India could pivot toward manufacturing with renewed competitiveness.

It could bring in foreign companies to set up manufacturing here. But that’s easier said than done. As many commentators have pointed out, India’s manufacturing sector has many challenges. Its labour-intensive manufacturing industries are overregulated. China is trying to kneecap Indian manufacturing. FDI, which could help its manufacturing efforts, is weak.

Thus, what it should focus on is building its own, China-esque tech-industrial complex. By combining government support with the network of Indian conglomerates, it could become an advanced manufacturing superpower like China. This would allow it to develop its own semiconductors, data centers, and energy infrastructure to become an independent, sovereign AI power.

We are already seeing shades of this. Reliance, one of India’s largest energy providers and oil refiners, is launching its own 30 Billion US$ datacenter. It will be powered by the cheap energy it has access to. Tata, the conglomerate behind TCS, is venturing into trailing-edge semiconductors and is building a 28nm to 110nm fab in collaboration with PSMC. Organising and augmenting such initiatives with large investments by the Indian government could be massively helpful.

However, the Indian government is far from an effective initiative. The IndiaAI programme is planning for 18,000 GPUs (Grok, a late 2024 model, trained on 200K GPUs). We need something at least ten times more ambitious, ideally forty or fifty times more ambitious to come close to French efforts, let alone American or Chinese ones. It doesn’t have to be flashy tech either. India doesn’t need to build Nvidia or OpenAI from scratch, it just needs to build Deepseek and Etched. India certainly has the state resources and technology to build an analogue of these two companies. Forget the state, even India’s startups could build something at that level.

Whatever path India takes, it must act decisively. India’s demographic advantages will begin to diminish soon, AI and its impacts will only become more profound, and the world will only become scarier and even more divided.

It can’t miss the boat, if only for the sake of its 1.5 Billion people.

Stay tuned for the sequel of this article — how India rescues itself from this nightmare.